Decades before women even had the right to vote, they were climbing to the top of the highest mountains in Europe and elsewhere – wearing skirts and corsets.

Lucy Smith and Pauline Ranken, members of the Ladies’ Scottish Climbing Club, climb the Salisbury Crags cliff in large boots and dresses. Edinburgh, 1908, colorized. Harnesses were unavailable to the group, and ladies had to climb in dresses to remain ‘decent.’

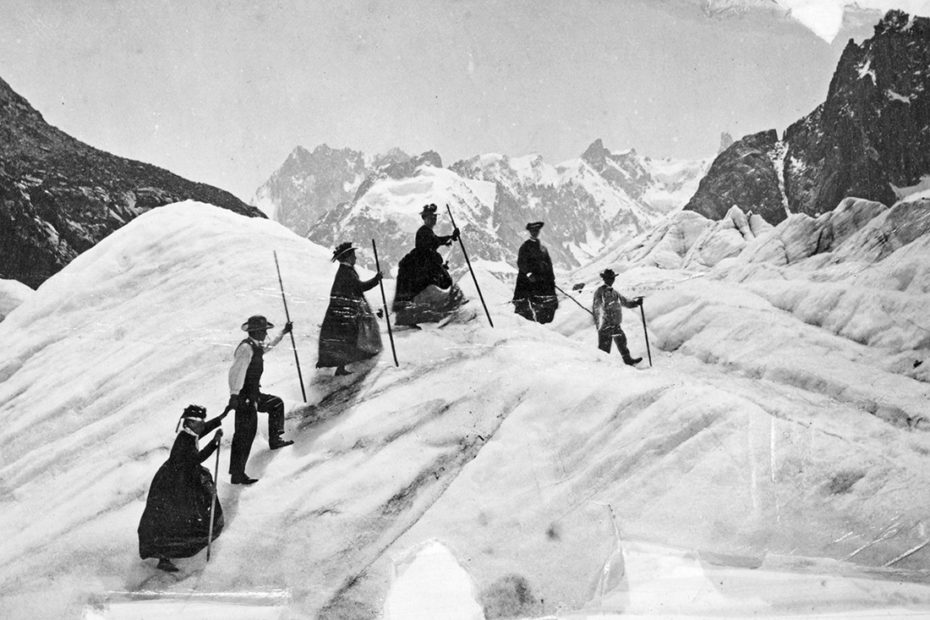

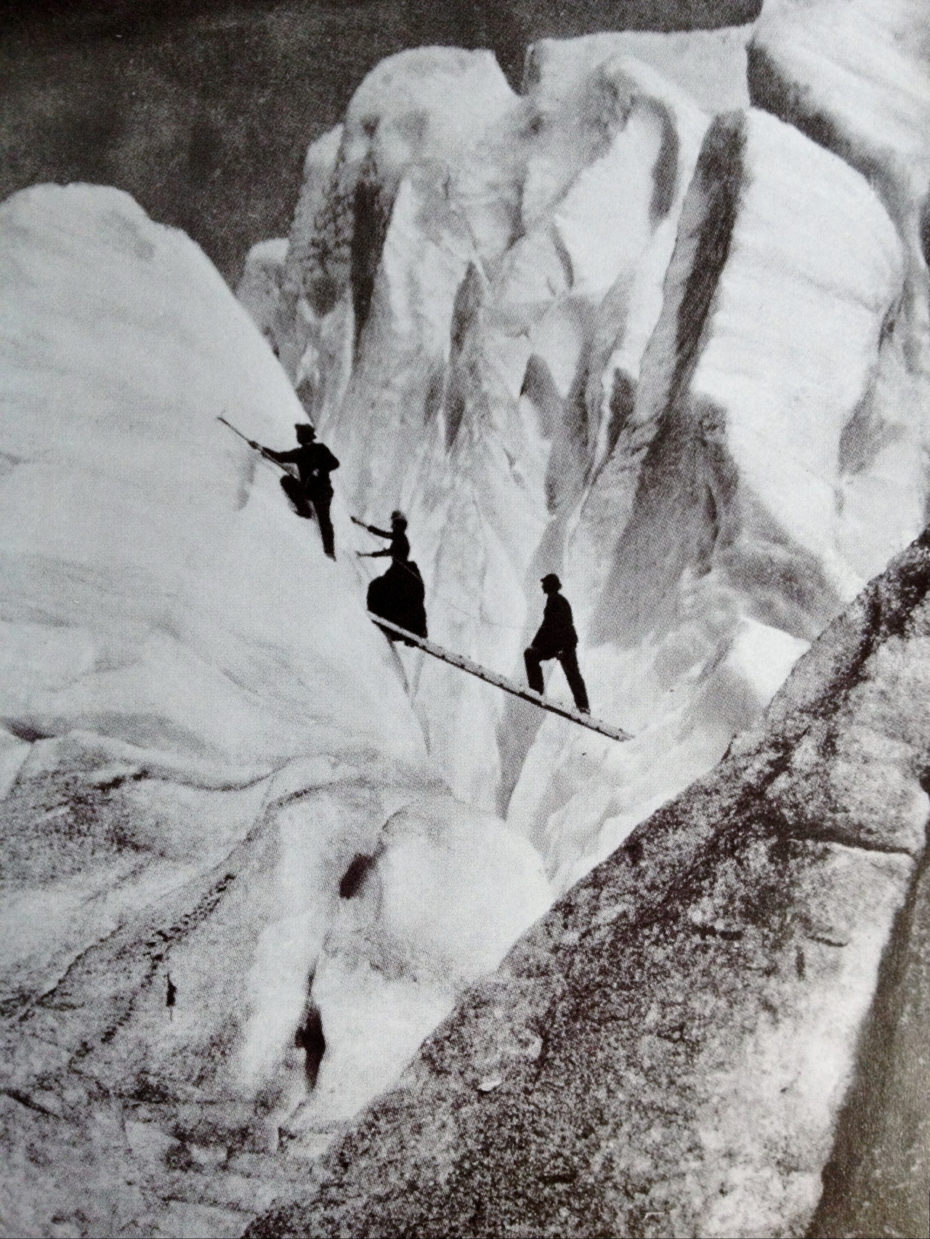

Consider for a moment, the below photograph of a woman climbing a glacier in a billowing Victorian skirt. Indeed, there were more than a few females who braved the ice in petticoats and traversed the world’s harshest environments at a time when a woman wearing trousers was still seen as seriously scandalous. So meet mountain climbing’s incredibly brave and capable pioneers!

Mary Isabella Charlet-Straton was a British female mountain climber, the first one in Britain to become famous as such. She made several first ascents in the Alps with Emmeline Lewis Lloyd as well as the first winter ascent of Mont Blanc with her future husband Jean Charlet in January 1876 (they climbed together for 20 years thereafter). This feat was published in many local and foreign newspapers, turning Straton into a climbing celebrity. The peak Pointe Isabella was named in her honor after she had taken part in its first ascent. A hotel in Chamonix, Pointe Isabelle, is themed around her many alpine adventures and accomplishments.

Isabella Charlet-Straton

But Charlet-Straton was not the first woman to ever climb Mont Blanc – the credit for that feat goes to Marie Paradis, a poor maidservant from Chamonix who climbed, rather reluctantly, Europe’s highest mountain as early as July 1808. She was no alpine enthusiast but, eager to quickly gain fame and fortune, ventured to climb it anyway. During the final ascent, she was in such poor condition that she had difficulty breathing, was unable to speak, and couldn’t see.

She was so exhausted and undone by her efforts that she begged her companions to throw her into the nearest crevasse to end her misery. “Throw me into a crevasse and go on yourself!” she wailed in devastating fatigue.

Nevertheless, Paradis was somehow dragged to the summit, eventually making it back from the mountain alive. In 1809 she recorded her experience in an “admirably graphic and picturesque” account and made quite a fortune out of her achievement, becoming known as “Maria de Mont Blanc”. According to some reports, after her own successful climb she left refreshments for others reaching the summit.

The second woman to successfully climb Mont Blanc was Henriette d’Angeville, who celebrated her successful ascent in Chamonix thirty years later. Interestingly, she was congratulated by Paradis, who had received her special, personal invitation. d’Angeville conquered the mountain in a self-made 7kg outfit (see below), and when she left for the summit from Chamonix, local men laced bets on which point of the ascent she would give up.

They proved to be wrong, however, as d’Angeville proved herself strong and agile enough. She climbed as well as the men, particularly on rock, though she did suffer from heart palpitations and drowsiness. When the party reached the summit, toasts were made with champagne, and doves were released to announce their success while d’Angeville was hoisted on the men’s shoulders and cheered. On their return to Chamonix, they were welcomed by a cannon salute.

Henriette d’Angeville dressed, as Mark Twain put it, “for the act”, wearing her self-made 7kg outfit.

How were these early climbers regarded by the rest of society? Well, consider the example of Miss Walker, who ascended the Matterhorn in Switzerland with her father in July, 1871. The Nuneaton Observer was scathing and claimed that this was not an “example to be followed,” for “Mountain-climbing is no woman’s work.”

But who was this Miss Walker? In a June 1898 article, the Evening Star called her “The doyenne of English lady mountaineers,” Lucy Walker being the “very first lady to climb the Matterhorn,” one of the highest summits of the Alps. They went on to describe how:

“With a modesty which distinguishes comparatively few mountaineers, Miss Walker denies that she has ever imperilled her life among the mountains, but declares that climbing completely cured her of rheumatism, from which she has suffered since her childhood.”

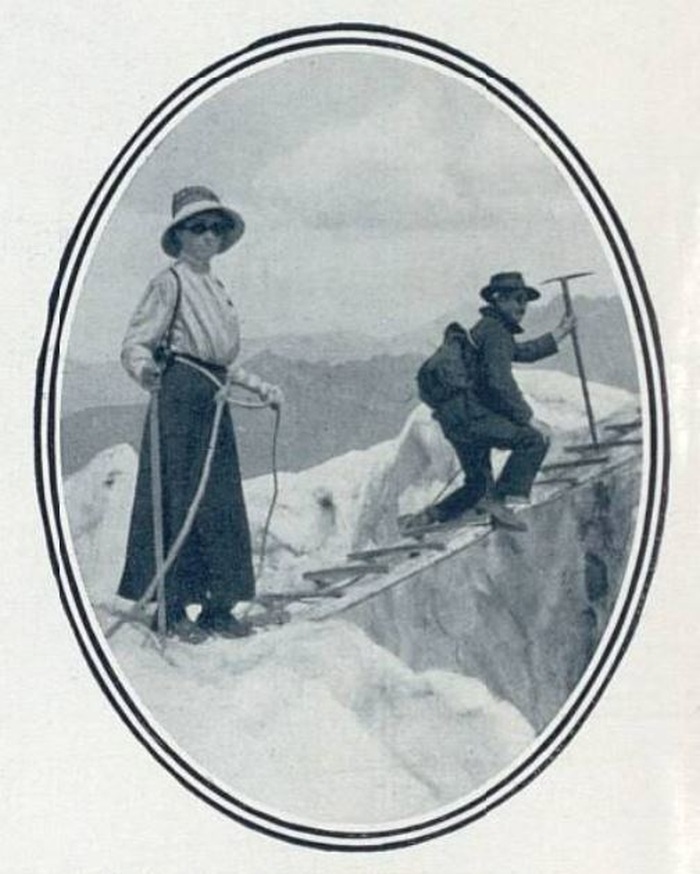

Today it’s hard to imagine how difficult it was for woman climbers to not only challenge the gender inequality and step out of the home in search of adventure and acknowledgment, but also to do it in skirts! In those times, most outdoor activities, sports and particularly mountaineering, were reserved for upper class men, which also meant that proper gear and equipment just weren’t available to women.

What is more, the strict Victorian dress etiquette required the first female mountaineers and explorers to climb wearing skirts and corsets “for modesty”, making their ascent to the summit much more difficult than it was for men. When American Annie Smith Peck decided to wear bloomers instead of a skirt on her climbs in the 1890s, a frightful scandal ensued, sparking public debate on whether women should even be allowed to attempt such activities.

Facing social repression, some female climbers turned their adventures into a platform for the women’s resistance. American geographer, cartographer, explorer, travel writer, and mountaineer, Fanny Bullock Workman, is a great example who set several women’s altitude records, while championing women’s rights and women’s suffrage. The famous photo above shows her in the Himalayas holding up a newspaper that reads “Votes for Women”.

Despite the serious inequalities and various disadvantages, women pressed on and female climbing became more and more accepted – not least because Queen Victoria was an avid mountaineer herself in her younger days. The founding of an all-women’s mountaineering club in Scotland (the Ladies’ Scottish Climbing Club, see first photo above), just a year after the Ladies Alpine Club in London was established in 1907, soon brought together like-minded ‘ladies’ who had a keen interest in mountaineering and went on to become pioneers in their day in many ways. To be decent, the members of these clubs also had to start their climbs in long skirts but, unlike their Victorian counterparts, they often discarded them to climb in knickerbockers when no men were around. And, of course, that too was to change soon, even though pants as an acceptable everyday clothing option for women didn’t truly catch on until the mid-20th century…