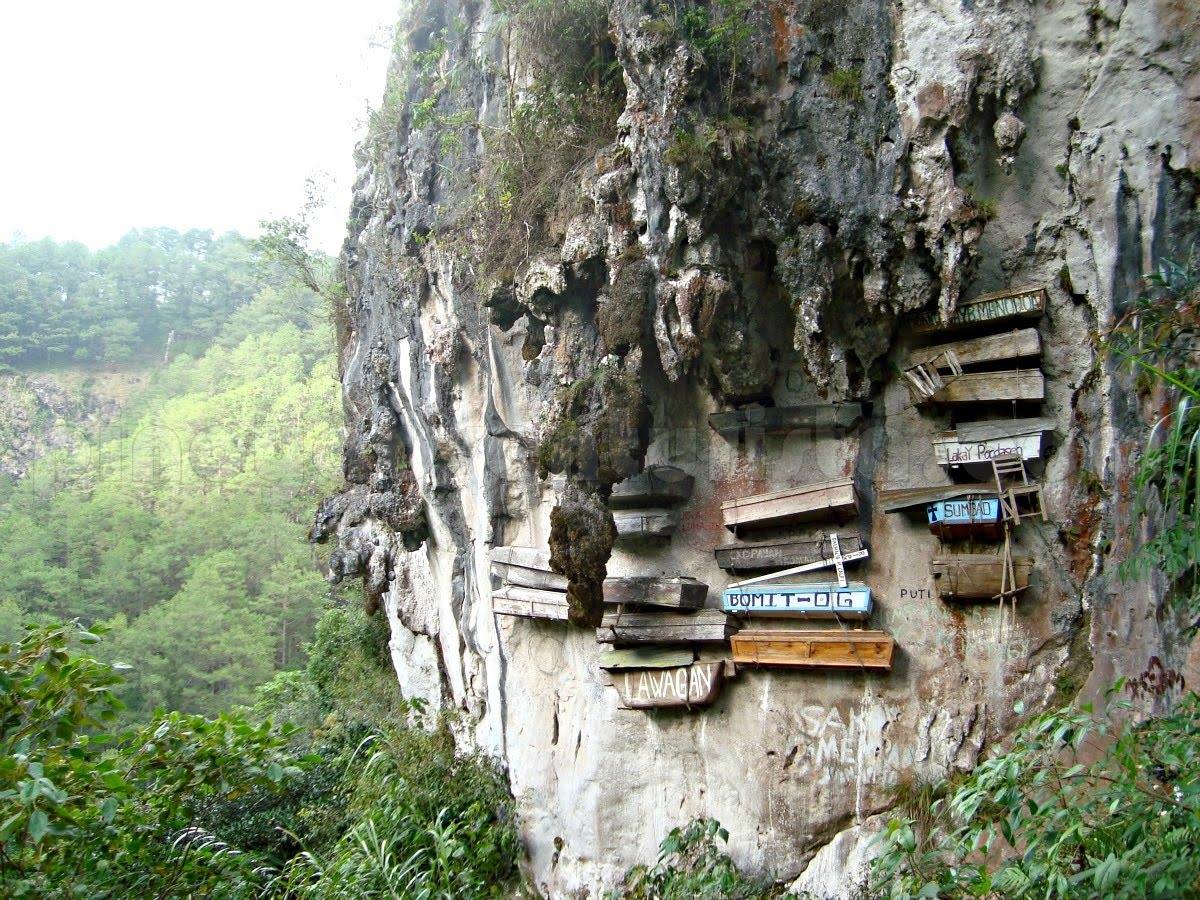

In Sagada, Philippines, the native Igorot tribe have been burying their dead in hanging coffins, attached to the sides of cliffs in the mountains of Luzon, for about 2000 years. According to their beliefs, this brings them closer to their ancestral spirits and would also keep their bodies safe from scavenging animals. Below are some rather eerie facts about this ancient burial practice.

Photo: Simon Gibson/via Facebook

Tourists visiting the hanging coffins of Echo Valley probably wonder what’s up with the wooden chairs strapped to the coffins. They are called sangadil, or death chair, and they are an important step in the traditional Igorot burial process.

Photo: Rick McCharles/via flickr

When someone dies, their corpse is tied to the chair using rattan and vines. Once propped-up securely in the chair, the corpse is covered with a blanket and placed in the deceased’s house, facing the main door. Over the next several days, relatives visit the corpse to pay their respect. In order to conceal the smell of decay, the cadaver is slow-smoked like barbecue brisket.

Photo: gogo159/via flickr

The spectactor would think that the smaller hanging coffins were for kids or babies, but that’s not the case. Traditionally, a corpse is buried in the fetal position, so you can “depart the same way [you] entered the world.” In order to fit a full-sized adult in a coffin just over three feet long, relatives have to break the bones of the dead.

So what’s up with the longer coffins then? According to an elder interviewed in 2014, these days many Igorots are “afraid to break the bones of their loved ones,” , so “very few” choose to go 100% traditional with the burial ritual.

Photo: Dr. Rainer Neu/via Wikimedia

Once the bones are broken into the fetal position, the corpse is wrapped like a basketball with another blanket and rattan and carried to the cliff. Traditionally, a small coffin that the deceased carved out of a hollowed out log before they died is waiting for the corpse (see one pictured above). On the way to the coffin, mourners swarm the broken corpse, hoping to get some blood on their hands. The blood is thought to bring success and pass on the skills of the deceased.

Photo: Jungarcia888/via Wikimedia

Following the rather gruesome process described above, young men from the village scale the cliff to hammer in the supporting mechanisms that hold the coffin in place. The coffins are either tied or nailed into the cliffs after the broken body is wrapped with vines and placed inside. Some of the oldest coffins (pictured above) are prone to falling and exposing the bones to tourists.

Photo by DEDDEDA/via PhotoShelter

The Philippines is a profoundly Christian country and the practice of burying the dead in hanging coffins is a dying art. An Igorot elder told Rough Guides in 2014 that these days, Igorot children “want to remember their grandparents, but they prefer to bury them in the cemetery and visit their tombs on All Saints Day.”